We're normally quite unaware of how our brain-machines enable us to see, or walk, or remember what we want. And we're equally unaware of how we speak or of how we comprehend the words we hear. As far as consciousness can tell, no sooner do we hear a phrase than all its meanings spring to mind — yet we have no conscious sense of how those words produce their effects. Consider that all children learn to speak and understand — yet few adults will ever recognize the regularities of their grammars. For example, all English speakers learn that saying big brown dog is right, while brown big dog is somehow wrong. How do we learn which phrases are admissible? No language scientist even knows whether brains must learn this once or twice — first, for knowing what to say, and second, for knowing what to hear. Do we reuse the same machinery for both? Our conscious minds just cannot tell, since consciousness does not reveal how language works.

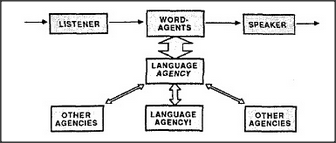

However, on the other side, language seems to play a role in much of what our consciousness does. I suspect that this is because our language-agency plays special roles in how we think, through having a great deal of control over the memory-systems in other agencies and therefore over the huge accumulations of knowledge they contain. But language is only a part of thought. We sometimes seem to think in words — and sometimes not. What do we think in when we aren't using words? And how do the agents that work with words communicate with those that don't? Since no one knows, we'll have to make a theory. We'll start by imagining that the language-system is divided into three regions.

The upper region contains agents that are concerned specifically with words. The lower region includes all the agencies that are affected by words. And in the center lie the agencies involved with how words engage our recollections, expectations, and other kinds of mental processes. There is also one peculiarity: the language-agency seems to have an unusual capacity to control its own memories. Our diagram suggests that this could be because the language-agency can exploit itself as though it were just another agency.