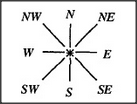

What's so special about moving left or right or up or down? At first one might suppose that these ideas work only for motions in a two- dimensional space. But we can also use this square-like frame for many other realms of thought, to represent how pairs of causes interact. What is an interaction, anyway? We say that causes interact if, when combined, they lead to effects that neither can cause separately. For example, by combining horizontal and vertical motions, we can move to places that can't be reached with either kind of motion by itself. We can represent the effects of such combinations by using a diagram with labels like those on a compass.

Many of our body joints can move in two independent directions at once — not the knee, but certainly the wrist, shoulder, hip, ankle, thumb, and eye. How do we learn to control such complicated joints? My hypothesis is that we do this by training little interaction-square agencies, which begin by learning something about each of the nine possible motion combinations. I suspect that we also base many of our nonphysical skills on interaction-square arrays because that is the simplest way to represent what happens when two causes interact. (There is even some evidence that many sections of the brain are composed of square arrays of smaller agencies. )

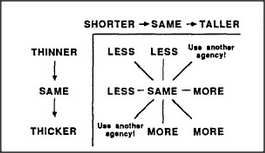

Consider that the Spatial agency in our Society-of-More is not really involved with space at all, but with interactions between agents like Tall and Thin. If you were told that one object A is both taller and wider than another object B, you could be sure that there is more of A. But if you were told that A is taller and thinner than B, you couldn't be sure which one is more. An interaction-square array provides a convenient way to represent all the possible combinations:

If square-arrays can represent how pairs of causes interact, could similar schemes be used with three or more causes? That might need too many directions to be practical. We'd need twenty-seven directions to represent three interacting causes this way, and eighty-one to represent four. Only rarely, it seems, do people deal with more than two causes at a time; instead, we either find ways to reformulate such situations or we accumulate disorderly societies of partially filled interaction-squares that cover only the most commonly encountered combinations.